By Denise Levine | (November 2014)

On August 29, 2001, The San Francisco Chronicle reported: “Fire forces evacuation of Trinity County town. Hundreds flee “totally chaotic scene in historic Weaverville.” The report went on to say the blaze, called the Oregon Fire, had quickly consumed 1,600 acres, forcing the closure of Highway 299. Smoke could be seen 24 miles away in Hayfork.

“It’s crazy out there,” said a CDF spokesman. “There are two heads on the fire, so it’s moving in two different directions. It’s ugly.”

But Carolyn and David Beans knew that. They lived on Oregon Mountain, just outside of Weaverville on the way to Eureka, California where the Oregon Fire was heading toward the 80 acres of Doug fir, sugar pine and incense cedar they owned.

David and Carolyn bought their first piece of land on Oregon Mountain in 1978. There was no electricity to the property, but there was a barn, a water tank and a propane generator in a shed.

They spent their first years off the grid, building their two story house in 1978, by hand. Foundation and framed doors and windows went in the first year, but there was no insulation and David reports it was more like camping. They built an outhouse out back, lights and refrigerator were powered by propane and heat and hot water were powered by solar and wood.

Throughout the years, the Beans added to their property, eventually aggregating 80 acres of contiguous property. A few years back, they gave 40 acres of it to their son, who now lives on the property next door with his wife and three children.

David’s background (a BS in Forestry from Humboldt State University and a 26 ½ year career as a property appraiser) was helpful as he put his Timber Harvest Plan (THP) together and logged his property from 1994-1996.

A successful harvest, the proceeds from the timber sales paid for Carolyn and David’s property in full. And finally, after living off the grid since 1978 they were able to afford the $40,000 cost of getting electricity to the property.

But then the Oregon Fire came.

The fire started just a quarter of a mile from the Beans’ property, and a fierce wind drove it toward their land. David is convinced that had the wind turned toward Weaverville, the town would be gone today.

The Deputy Sheriff drove out to the Beans’ property to make sure they were safe, and David sent Carolyn to town with him, while David, with forestry and fire fighting experience, stayed behind to try to save the property. Alone, David climbed the hill, surveyed the quickly moving fire and determined he could not save the land. He needed to try to save the house.

And then it became clear he could not do that, either. With the fire quickly approaching, David found a swale in his back lawn, and flattened himself against the ground. The fire passed over him.

A while later he tried to walk to the nearest road but the ground was too hot. A few hours later, he made it to the road, and walked almost two miles before a local firefighter, who also happened to be the coroner, passed by and picked him up.

I could hear David smiling as he related hopping out of the back of the Coroner’s SUV to reunite with Carolyn. This might be a story to ask to hear in person at the FLC conference next year in Auburn. My conversation was with David, but I am sure that Carolyn has some stories to tell, too.

The effects of the fire were disastrous. The house was gone. The black smell of smoldering wood hung over everything. Remaining stumps of trees slowly burned for the next year, deep in the soil, where no amount of water could extinguish the smoldering roots. The Beans’ discussed whether or not they had the energy to begin again. According to David, Carolyn was ambiguous, but David was sure he could replant and rebuild.

David reports State Farm was great, and their fire insurance policy soon had their house rebuilt. But the policy did not cover the trees. With a Salvage permit, David harvested and salvaged what wood he could.

Then, working with the Natural Resource Conservation Service and funded by EQIP grant money, the Beans began the restoration of their property. First the brush had to be cleared and then discouraged from reappearing. David used a combination of burning and spraying. Then the property was replanted with cedar and pine. The trees grew quickly and made good progress.

Then the Weaverville fire of 2006 went through, and burned everything down again.

Once again the house was rebuilt. David had used part of the EQIP money after the first fire to pay for help to replant his property, but this time David replanted the trees himself.

EQIP funds and a relationship with the NRCS were helpful and productive. Compensation for work completed was prompt, and this helped speed the restoration along.

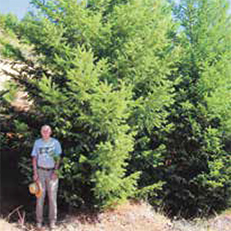

Replanting is not a one-time thing. Since trees are dry farmed, David told me the young trees, planted as container stock, face an uphill battle. Damage from browsing deer is a typical problem, and more trees survive wet years, than the dry, drought years we have been experiencing. In a wet year, the trees can grow a foot a year.

Life goes on out on Oregon Mountain. David’s and Carolyn’s property is green and growing once again and the latest trees are close to 12 feet tall now. The land now hosts three ponds of water reserves and David has had the property rezoned as a Timber Production Zone (TPZ). He and his family plan on living on the property for a long time.

Upcoming Events